The Stream

Your life. My life. And the nature of the universe.

Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

Click open the video, below

Sit with it for awhile

Turn up your speakers

You’re watching the universe. “The indivisible and un-analysable wholeness in flowing movement,” in the words of physicist David Bohm. The universe in torrential motion on YouTube, if you like.

You’re not a spectator — the observer seemingly standing outside it, commenting on it. Quantum physics teaches us that there is no such thing as a spectator. By merely looking at something or thinking about it or commenting on it, you influence it — you change it. Whether you like it or not, whether you acknowledge it or not, you are profoundly participating in and shaping the universe in equal measure as it participates in you and shapes you.

Come, get into this canoe. We’re going to paddle out into this “wholeness in flowing movement” so I can demonstrate how you participate in it. Before we do, I ask you to lay aside everything you’ve believed about death and dying. You can retrieve all that stuff later. In the Stream, where we’re headed, most of what you’ve been taught or thought is either irrelevant or dead wrong.

(Don’t worry about life preservers; in this journey, of all journeys, they’re unnecessary. You’re already capsized in this.)

First, some physics background as we head into the current, again taking our cue from David Bohm. (Bohm died — rejoined the Stream — in 1992. American-born and Berkeley-trained, he was a major theoretical physicist, teaching for most of his career in the U.K.) Bohm argued that it’s pointless to search for the ultimate “elementary particle” — the God principle. “Flow” — the Stream — he wrote in a brilliant insight, trumps elementary particles. “Flow is in some sense prior to that of the ‘things’ that can be seen to form and dissolve in this flow.” (Stay with me; this will begin to make sense in a moment.)

He named this cosmic flow the “holo-movement,” though I prefer calling it the Stream — no different, frankly, from my Adirondack streams and brooks. (“Holo-movement” means “the entire movement” or “the movement of everything.”)

The best image . . . is perhaps that of the flowing stream, whose substance is never the same. On this stream, one may see an ever-changing pattern of vortices, ripples, waves, splashes, etc., which evidently have no independent existence as such. Rather, they are abstracted from the flowing movement, arising and vanishing in the total process of the flow. Such transitory subsistence as may be possessed by these abstracted forms implies only a relative independence or autonomy of behaviour.

Of course, modern physics states that actual streams (e.g., of water) are composed of atoms, which are in turn composed of “elementary particles,” such as electrons, protons, neutrons, etc. For a long time it was thought that these latter are the “ultimate substance” of the whole of reality, and that all flowing movements, such as those of streams, must reduce to forms abstracted from the motions through space of collections of interacting particles. However, it has been found that even the “elementary particles” can be created, annihilated and transformed, and this indicates that not even these can be ultimate substances but, rather, that they too are relatively constant forms, abstracted from some deeper level of movement.

— David Bohm, from “Wholeness and the Implicate Order”

Nothing — no thought, experience, event, force or power or god or good or evil, or mouse for that matter — exists outside the holo-movement that silently, inexhaustibly, ever so patiently pours through everything. As if “woven into us, deep and magical,” borrowing a line from Rilke.

In the Eighth Elegy, Rilke laments how “almost from the first we take a child

and twist him round and force him to gaze

backwards and take in structure, not the Open

that lies so deep in an animal’s face. Free from death.

Only we see death; the free animal has its demise

perpetually behind it and before it always

God, and when it moves, it moves into eternity,

the way brooks and running springs move.

By nature, children are dissolved in the consciousness of the Stream. This being their First World, their natural awareness, says Rilke, who calls it the Open. “Never, not for a single day,” he goes on, “do we

have that pure space ahead of us into which flowers

endlessly open. What we have is World

and always World and never Nowhere-Without-Not:

that pure unguarded element one breathes

and knows endlessly and never craves.

As a child

one gets lost there in the quiet, only to be

jostled back.

The Open. The Nowhere-Without-Not. That pure unguarded element one breathes and knows endlessly and never craves. This is what I call the Stream. Spend some time with a young child and you will understand what Rilke and I are talking about.

Notice, I didn’t say the stream you’re watching or my Adirondack stream is a metaphor of the universe. It is the universe. It shapes me as I write these words — literally my hand and thoughts. And shapes you as you read this.

Before you were born and yes, after you die, you are the Stream. The river (borrowing again from Rilke) “that dwells whole at the core of all things. . . . Its great pulse . . . parceled out among us into tiny beatings.”

This water ran and ran, incessantly it ran, and was nevertheless always there, was always and at all times the same and yet new in every moment! Great be he who would grasp this, understand this! He understood and grasped it not, only felt some idea of it stirring, a distant memory.

— Hermann Hesse, from “The Ferryman,” Siddhartha

One can never not be the Stream, both part of it and in some ineffable way, all of it. (Consider this Lesson #1.)

Writing of himself in the third person, Rilke recalled a moment when the Stream “passed into him so intimately from every side, that he could believe he felt the light reposing of the already appearing stars within his breast.” He had closed his eyes, “so as not to be confused in so generous an experience by the contour of his body.”

It happened as he meditated in a garden, triggered by nothing more portentous than birdsong.

He remembered the hour . . . when, both outside and within him, the cry of a bird was correspondingly present — did not, so to speak, break upon the barriers of his body, but gathered inner and outer together into one uninterrupted space, in which, mysteriously protected, only one single spot of purest, deepest consciousness remained.

To live “dissolved in deepness” is our birthright (Rilke).

Look for it in water. “If there is magic on this planet,” mused Loren Eiseley, “it is contained in water. . . . Its substance reaches everywhere; it touches the past and prepares the future; it moves under the poles and wanders thinly in the heights of air.”

No utilitarian philosophy explains a snow crystal, no doctrine of use or disuse. Water has merely leapt out of vapor and thin nothingness in the night sky to array itself in form. There is no logical reason for the existence of a snowflake any more than there is for evolution. It is an apparition from that mysterious shadow world beyond nature, that final world which contains — if anything contains — the explanation of men and catfish and green leaves.

The tricky word is “form.” We are fixated on form and structure. Blinded by them. Just as particle physicists were by the “building blocks” model of reality. We celebrate the creation of form — birth. We follow the changing of form — maturation. And mourn, at last, the extinguishment of form — death. All the while oblivious to the Stream that molded each form and cascades through it. (Look at the stream in the video, above, or this one, below.)

Turtle and fish and the pinpoint chirpings of individual frogs are all watery projections, concentrations — as man himself is a concentration — of that indescribable and liquid brew which is compounded in varying proportions of salt and sun and time. It has appearances, but at its heart lies water.

As for men, those myriad little detached ponds

with their own swarming corpuscular life, what were they but a way that water has of going about beyond the reach of rivers? . . . Thoreau, peering at the emerald pickerel in Walden Pond, caIIed them “animalized water” in one of his moments of strange insight.

— Loren Eiseley, from “The Immense Journey”

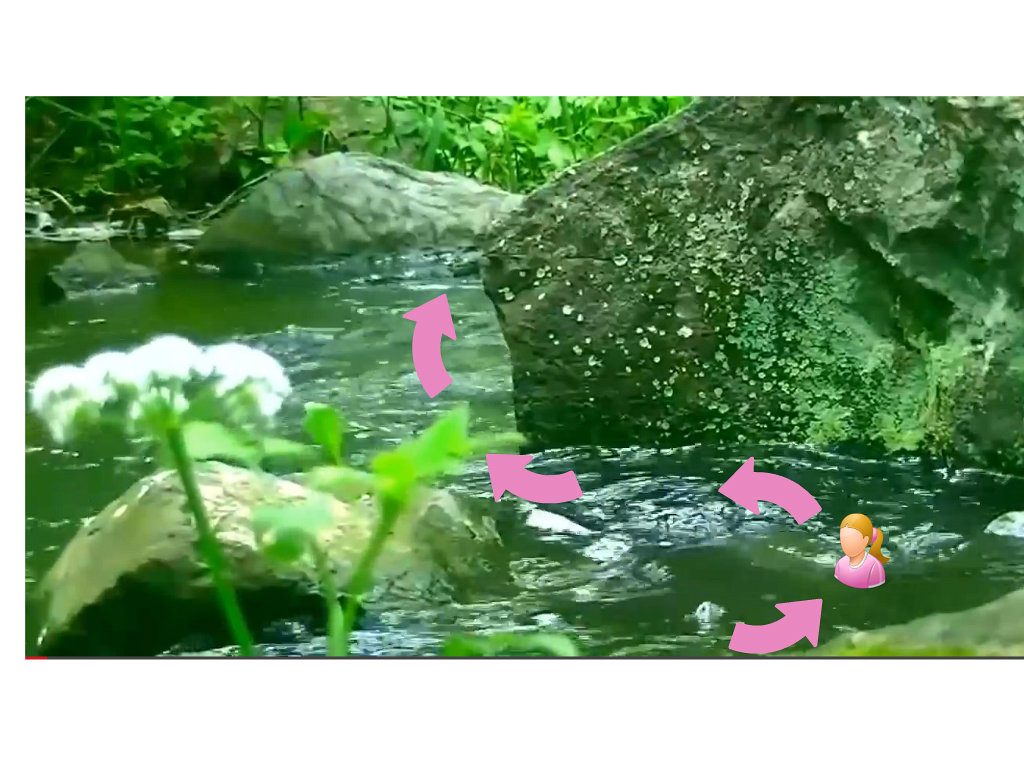

Look closely, now, at this image captured from yet another video, which, alas, has been removed from YouTube, so I can’t embed it here. (A static image contradicts the principle of the Stream, of course, but bear with me for this little exercise.) The white arrow shows where I erased a bit of turbulence — a riffle, an eddy. Focus on this particular spot.

Something is about to happen. Before it does, I ask you to indulge me. Pretend the video starts off with no turbulence at this spot. Pretend there’s nothing to distinguish this stretch of water from any other flat, smooth surface in the stream.

And yet the Stream is eternally coursing through that unremarkable spot, though imperceptible to the eye, since our eye can’t detect the current beneath the surface. This is Lesson #2.

Then the miracle. I inserted a vortex as a kind of Star of Bethlehem over the place where Stream is about to change shape — form itself into a singularity. Into a person — a seemingly fixed yet in fact fluid event in the ways of Stream.

It you were to look at the video, you would see a vortex at that spot. Perhaps a standing wave. The Stream has given birth to a new event; a child is born. (Notice the vortices and standing waves in the far right video.)

A human life created from the flux and ways of the Stream.

When there were clean storm windows

and new small eggsI gave birth to an autumnal girl.

Some nights still

I feel the warmth of

a harvest moon

on the nape of

her neck.Always she dances with

the grace

of dangling goldenrod

(who knew yellow velvet could be worn

so freely),and delicacy

of wide eyed asters

speckled about.Eyes, they say, everyone says,

“unspeakable, unreachable, deep lake water”

amid milkweed hairand if you meet her spirit —

it will be playing about —

running fingers / Up washboard clouds,

skipping through puddles and

humming [off] rhythms,that please her

— Esther Wrightman

The child thinks she lives in “the region of Always” — the Stream.

She is of course right.

Until she’s taught that she is wrong.

This inclination, in the years

when we were all children,

to be so much alone, was gentle;

for others time passed in fighting,

and one had one’s faction,

one’s near, one’s far-off place,

a path, an animal, a picture.And I still imagined that life

would never cease providing,

while one dwelt on things within.

Within myself am I not in this greatness?

Will what’s mine no longer soothe

and understand me as when a child?Suddenly I’m as if cast out,

and into something vast and ill-fitting

this solitude transforms,

when, standing on my breasts’ hills,

my feeling screams for wings

or for an end.— Rilke, “Girl’s Lament”

She thinks she lives in grace

(the Stream) — and of course she

is right.

Until she’s taught she is wrong.

Every spring

among

the ambiguities

of childhoodthe hillsides grew white

with the wild trilliums.

I believed in the world.

Oh, I wantedto be easy

in the peopled kingdoms,

to take my place there,

but there was nonethat I could find

shaped like me.

So I entered

through the tender buds,I crossed the cold creek,

my backbone

and my thin white shoulders

unfolding and stretching.

From the time of snow-melt,

when the creek roared

and the mud slid

and the seeds cracked,I listened to the earth-talk,

the root-wrangle,

the arguments of energy,

the dreams lyingjust under the surface,

then rising,

becoming

at the last momentflaring and luminous —

the patient parable

of every spring and hillside

year after difficult year.— Mary Oliver, “Trilliums”

Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs

About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green,

The night above the dingle starry,

Time let me hail and climb

Golden in the heydays of his eyes,

And honoured among wagons I was prince of the apple towns

And once below a time I lordly had the trees and leaves

Trail with daisies and barley

Down the rivers of the windfall light.

………………………

In the sun born over and over

I ran my heedless ways,

My wishes raced through the house-high hay

And nothing I cared, at my sky blue trades, that time allows

In all his tuneful turning so few and such morning songs

Before the children green and golden

Follow him out of grace.— Dylan Thomas, from “Fern Hill”

The child becomes a woman for whom “the heaviness of life” is often “heavier even than the weight of things” (Rilke).

Even so the Stream — unbidden, unchanged, unfettered — plunges through her. “I effuse my flesh in eddies and drift it in lacy jags.” Walt Whitman wrote that.

Read “Leaves of Grass” and you can’t help but notice how deeply Whitman understood the Stream and knew, absolutely knew, he was everywhere in it.

David Bohm reaffirms Whitman’s lyrical credo, “Wholeness permeates all that is being discussed, from the very outset.” Somehow we are the whole Stream.

Bohm was a hard-core physicist who made notable contributions to our understanding of cosmology — the ultimate nature of reality. Intellectually (often literally, for he taught at Princeton for a time) he rubbed shoulders with the likes of John Archibald Wheeler, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and Einstein — scientists who spent a lifetime in search of the Holy Grail of reality, only to find it to be fairy gold. “Untouchable, impenetrable, impalpable,” Wheeler wistfully put it.

Even so, every one of these men would agree with Bohm — somehow, we are the Stream.

To Whitman, it was obvious: “I incorporate gneiss, coal, long-threaded moss, fruits, grains, esculent roots.” Which is hardly surprising. Poets, like physicists and alchemists before them, have always been drawn to the thin, intoxicating atmosphere of the “amassing harmony” (Wallace Stevens). Not through the cold calculus of numbers, but through the genius of the Word.

In the poetry of W.H. Auden the Stream is the “garden,” the “miracle,” the boundless “real” like that which ravished Rilke.

For the garden is the only place there is, but you will not find it

Until you have looked for it everywhere and found nowhere that is not a desert;

The miracle is the only thing that happens, but to you it will not be apparent,

Until all events have been studied and nothing happens that you cannot explain;

And life is the destiny you are bound to refuse until you have consented to die.

Therefore, see without looking, hear without listening, breathe without asking:

The Inevitable is what will seem to happen to you purely by chance;

The Real is what will strike you as really absurd . . .

—W.H. Auden, from “For the Time Being”

T.S. Eliot, Auden’s contemporary and another outspoken anti-temporalist, famously called it the “still point.” “Neither flesh nor fleshless / Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is.” Where “the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, unremembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning— T.S. Eliot, from “Little Gidding”

Know the place for the first time? Not really. Children know this place. Which is why Rilke struggled to remember that child. (His “Unfinished Elegy” bears witness to his struggle.)

“At the approach of age some men look about them at last and discover the hole in the hedge leading to the unforeseen. By then, there is frequently no child companion to lead them safely through”

— Loren Eiseley

Mary Oliver never forgot the child.

I thought the earth

remembered me, she

took me back so tenderly, arranging

her dark skirts, her pockets

full of lichens and seeds. I slept

as never before, a stone

on the riverbed, nothing

between me and the white fire of the stars

but my thoughts, and they floated

light as moths among the branches

of the perfect trees. All night

I heard the small kingdoms breathing

around me, the insects, and the birds

who do their work in the darkness. All night

I rose and fell, as if in water, grappling

with a luminous doom. By morning

I had vanished at least a dozen times

into something better.

— Mary Oliver, “Sleeping in the Forest”

It is said that Jesus of Nazareth likewise didn’t forget. They say he taught that only when we become like children, again, can we regain the consciousness of the Stream — the Kingdom of Heaven, his followers called it.

Elsewhere, he instructed a perplexed theologian that to live consciously in the Stream we must somehow be reborn of “water and the spirit.”

3 thoughts on “The Stream: Part 1”

This speaks to me of non-duality and the oneness (stream) of all that IS. It seems to me that we may have failed to understand this because we have forgotten how to look and feel beyond thought and the perception of the 5 senses.

Looking forward to your thoughts in the next segment.

Regards,

Tim

A lot to grasp, here; easier, however, than trying to figure today’s world.

My best times were as a child and I constantly look back, when times appeared to be simple.

My life seems to be complicated when I allow others to attempt to influence me.

As I type, I hear the strength of the ocean waves in the background. The power seems overwhelming and, yet, still peaceful.

This is when I am at peace. Today’s world draws you to the edge, where you feel completely helpless.

The older I get the stronger I believe that as a child was when I was happiest.

Watching my grown children shows me my past, growing up. Watching my grandchildren brings me to the happy times in my life and produces a slight smile.

Bruce Lee once said, “Be like water!”

I am awaiting part two.

I am at peace. Thank you!

.

Editors reply: Thank you, my dear.

Beautiful. River. City? City of the river?