1914: Dancin' at Elm & Main

Start dancin’. Better yet, grab your partner (spouse? companion? anyone handy?) and improvise. The charleston, turkey trot, fox trot, black bottom, or whatever works.

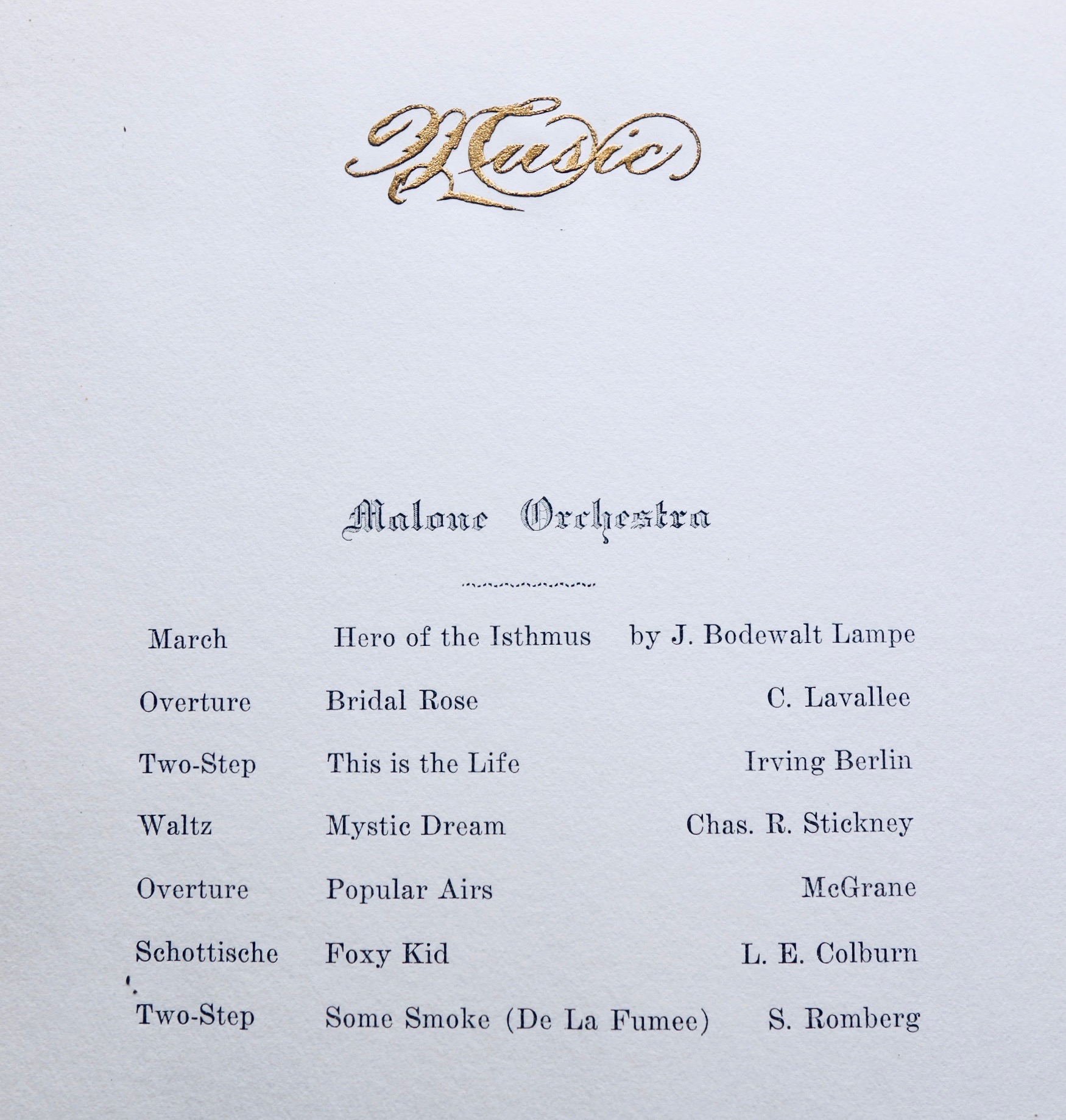

Ready for this?! You’ve been dancing, my dear, to the Malone Orchestra. The orchestra is long dead, of course; you’re dancing to the rag-time they played at a grand celebration on July 1, 1914.

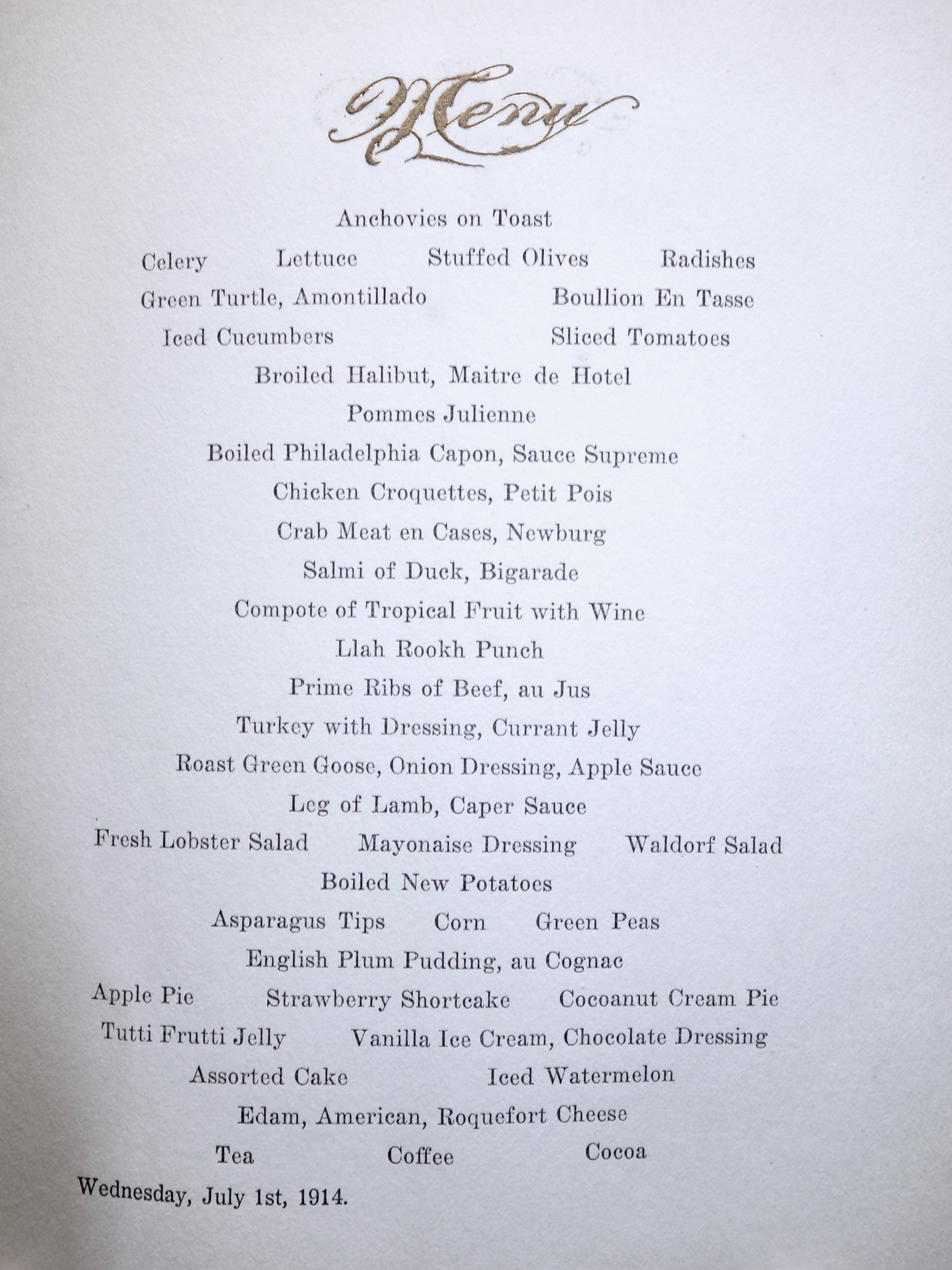

Image a balmy summer evening. The high society of “Malone, Star of the North since 1802” has turned out for an evening of dance, laughter, booze (Prohibition is 6 years away), and spectacular dining.

They arrive in the new horseless carriage: Henry Ford’s “Tin Lizzie” Model T Depot Hack, the rakish Regal Underslung Touring Model N, and a host of others.

The music is loud, the laughter raucous, the liquor flows freely and is nothing but the best. The hosts, Samuel J., John A., and Joseph J. Flanagan, are determined to make the grand opening of their new hotel a smashing success. And, yes, there is “some smoke.” After all, it’s the golden age of tobacco.

Live orchestra, booze, and then came the food.

Turkey with Dressing, Currant Jelly

Prime Ribs of Beef, au Jus

Apple Pie

Assorted Cake

Note the date at the bottom of the menu. Wednesday, July 1, 1914. Four days before, on Sunday, a 19-year-old revolutionary assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, while the duke and his wife (also assassinated) were visiting Sarajevo, Bosnia. Two rounds from a Browning semi-automatic were all it took to unleash the hounds of war. By the end of July the Great War that would devour all of Europe and slaughter virtually an entire generation, was on. The global flu pandemic toward the end of the war contributed markedly to the mortality.

Some quick to arm,

some for adventure,

some from fear of weakness,

some from fear of censure,

some for love of slaughter, in imagination,

learning later . . .

some in fear, learning love of slaughter;

……………………………………………………

Daring as never before, wastage as never before.

Young blood and high blood,

Fair cheeks, and fine bodies;

……………………………………

There died a myriad,

And of the best, among them,

For an old bitch gone in the teeth,

For a botched civilization . . .

— Ezra Pound1

Europe would never be the same. Indeed Western civilization would never be the same. America officially claimed neutrality while supplying Britain and its allies with war materiel. In 1917 we ended the pretense of neutrality and declared war on Germany, sending 4 million soldiers into the trenches of France, Belgium, and Germany, where 110,000 perished.

Some of the young revelers at the Flanagan that July evening are undoubtedly among those who “walked eye-deep in hell”2 and now lie buried in fields where “poppies blow / between the crosses, row on row.”3

On the face of it the christening of the Flanagan seemed to signal a grand future for Malone. The town had finally come of age and could boast the biggest and perhaps finest hotel between Albany and Montreal. Only by hindsight can we discern what really happened that fateful summer — the summer of World War 1, the summer of the Panama Canal, and the summer of the Flanagan.

The new Hotel Flanagan, on the site of the old Miller House, and the most modern and probably the largest hotel in Northern New York, was begun in 1913, and opened in July, 1914, by Samuel J., John A. and Joseph J. Flanagan. It contains over a hundred rooms, and every item of equipment is high class. The cost of the house, including site, was over a hundred thousand dollars.

-- from Frederick Seaver, "Historical Sketches of Franklin County" (1918), p. 458

World War 1 was not caused by 2 bullets. Think of it more as a supernova, the violent death of a once great star, in this case the violent implosion of decadent, obsolete empires — Ezra Pounds’s “old bitch gone in the teeth.” More importantly for the topic at hand, the war marked America’s entry onto the world stage as a major player, militarily, economically, and culturally. Think of WW1 as the opening fireworks of the “globalist” economic movement.

The timing of the Panama Canal was perfect for the new international vision. America now had ready access to Asian markets via the canal. The canal also meant we could deploy our navy to the Pacific theater if we wished.

One might argue that in the summer of 1914 America became open to business in a way it had never before known. First there was the business of overseas war; for war, after all, can be very profitable if one plays one’s cards right, as America did. Then there was the business of trade and commerce following the war.

For the next 50 or so years, Malone’s manufactures (shoes, clothing, etc.) would flourish from lucrative global and domestic markets. The railroads were critical. Malone and its swanky temple of affluence, the Hotel Flanagan, prospered mightily. (Just look at all the fine old homes, including mine.)

But the handwriting was on the wall. By the last quarter of the century, Malone was feeling the pain of free trade agreements and “out-sourced” labor — corporate management’s response to labor unions and the rising expectations of a burgeoning middle class.

Fast forward to the late 1990’s, when my wife and I moved here. The railroads were long gone, Tru-Stitch had shunk to a dozen or so staff occupying a dingy warehouse down by the river, and out-of-town slumlords were snapping up elegant old homes and turning them into DSS-subsidized hell-holes.

Malone, like other landmark mill and mining towns across America, was in a death spiral.

Within days of moving in, we were awakened in the night by a spectacular fire. A seedy hotel calling itself the “Flanagan” had been torched by a derelict.

A moment ago I said WW1 didn’t start with two bullets. Just so, the Flanagan didn’t end with a match. It ended when the 50-year bubble of middle class prosperity ended in America.

That era will never come back. Which is but another way of saying Malone’s historic district is over. Finished. All those buildings were created and sustained by a culture and society that are irretrievable, because the economic bubble that created both the culture and society is burst.

Pop! It’s over. We can’t simply “fill” these buildings with shops and businesses. That’s like driving your Tesla into a gas station and telling the attendant, “Fill ‘er up!” A “shop” and a “business” are extensions of a culture and society and the market forces that underpin them. America long ago junked the business model that would turn the downtown corridor into this, once more.

The Flanagan is a relic of this cold fact, like a washed-up shipwreck from long ago. Malone reminds me of a man gasping and struggling through life with a corpse lashed to its waist— the corpse of this burned-out building and everything it represented.

Bury it, for god’s sake! Take it down. To invoke “historic value” is absurd in the extreme. Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral has historic value; the Flanagan does not. Waiting for that building to be born again is like waiting for the Second Coming. Much better to get on with reality and create our own renaissance (“rebirth”), rather than look to dead buildings in the childish fantasy they will somehow come alive and we will all live happily ever after.

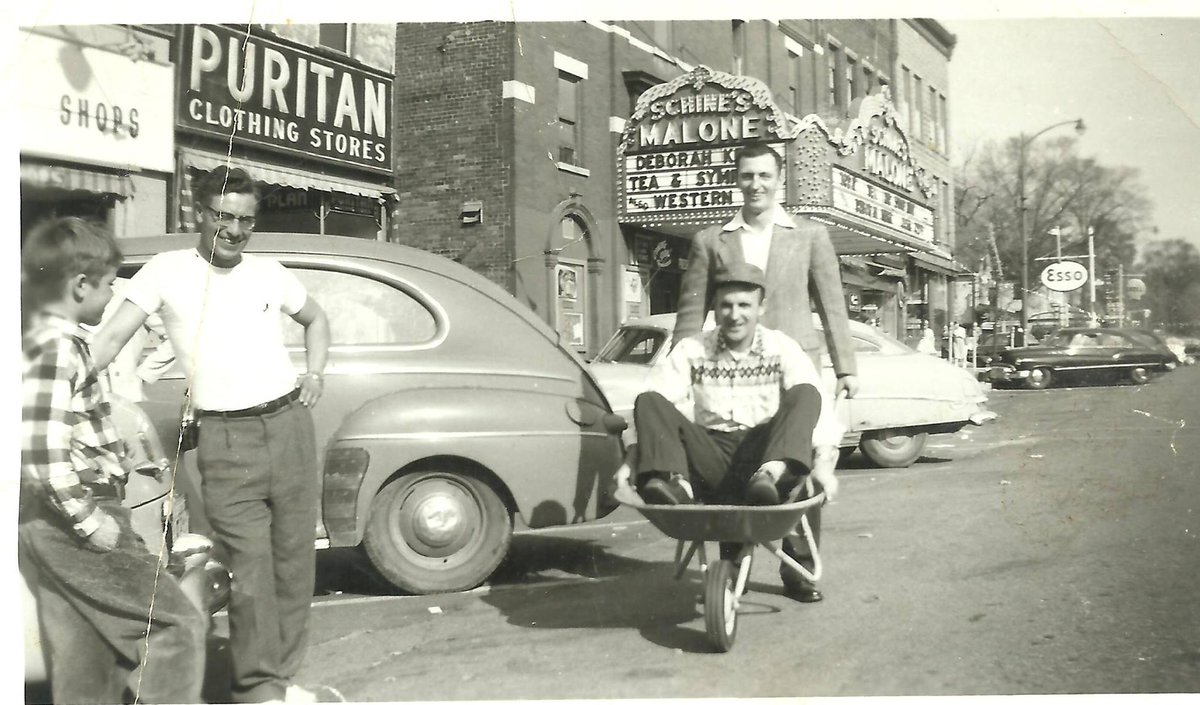

Examine the photo to the right. (Judging from the fins on those cool cars, it looks like the early Sixties to me.)

Yep, it’s the massive office building (with rental apartments upstairs?) that occupied the block between Washington and Clay Streets, Malone.

One winter’s night when the thermometer read 20 below and, as it happened, Town Supervisor Andrea Stewart was 6 months pregnant, that entire block went up in “some smoke.” (Note the red arrow. That’s Fireman Andrea next to her husband, Fireman Brent. Andrea wasn’t supervisor, then.)

Instead of leaving this charred and gutted wreck standing for its supposed historic value, or letting it stand in the hope some out-of-town “investor” might fix it up and turn it into cafés and cute shops — the town or the owner had the good sense to tear it down.

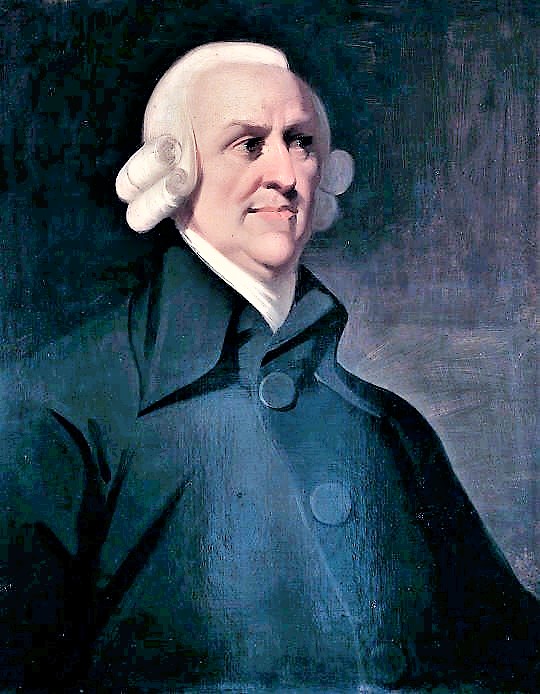

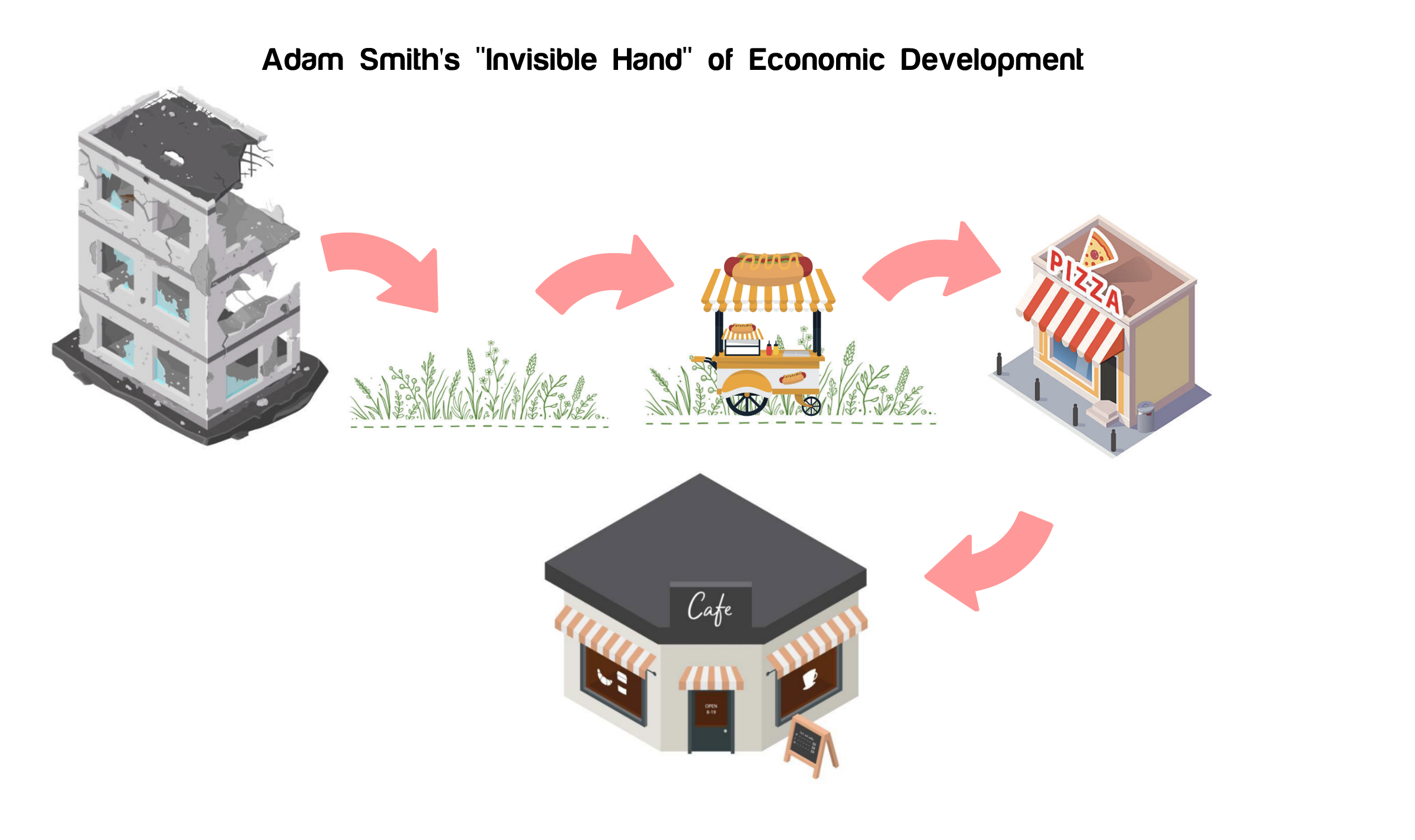

When I moved here, that parcel of land was dirt. A weed patch. Then, by golly, John Shea moved in a hot dog stand. (“Hooray! Civilization was returning to this barren wasteland between Clay & Washington!”) Then Harold Tebo moved in a vegetable stand. (“Hooray! More signs of life!”) Then the North Franklin Federal Credit Union moved a trailer onto one of the lots and opened its doors for business. The trailer was soon replaced by a fine office building. The lot next door was transformed into a fine medical office complex. Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” of economic development was doing its thing! (Click the drop-bar, below, for Smith’s explanation of the “invisible hand.” Only a nerd like me would want to read this.)

The following is taken from Adam Smith's "Wealth of Nations" (1776), wherein he explains (more or less) what he meant by the "invisible hand" of a free marketplace. (Quoted from Wikipedia.)

But the annual revenue of every society is always precisely equal to the exchangeable value of the whole annual produce of its industry, or rather is precisely the same thing with that exchangeable value. As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value, every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was not part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it.

Adam Smith

18th century Scottish philosopher and father of modern economics. Author of "The Wealth of Nations" (1776).

Here's how the "invisible hand" of the free marketplace can take us to a new life beyond the Flanagan

Here’s a rough idea of the taxes the Village of Malone would get from each stage of economic development of that lot.

References:

- Ezra Pound, from “E. P. ode pour l’élection de son sépulchre,” in New Selected Poems & Translations (New Directions, 2019), p. 113.

- Pound, p. 113.

- John McCrae, from “In Flanders Fields.”

1 thought on “1914: Dancin’ at Elm & Main”

Loved it! Great job! My cousin Gerald Reome, Toby Cook, and my uncle Ray Tatro pushing my uncle Larry Reome in the wheelbarrow down East Main Street! Ray’s brother, Gerald, would eventually buy the Dixie Lee from Preston Miller and later change the name to Mister T’s.

I was at the U.S. Border Patrol Academy in Glynco, Georgia when that fire started! I worked for my uncle for a year while it was still Dixie Lee!

Funny how everything comes full circle!